Having checked with a couple of friends, we decided to go to the Almazara or olive press about ten minutes from where we live.

“You can’t miss it,” and “It’s dead easy” are usually precursors to much futile effort and getting lost, but we had crates of freshly picked olives and we needed to be brave.

We were pleasantly surprised to find that we didn’t miss it. It would have been difficult, considering the huge signage, the enormous array of machinery and the queue of vehicles, loaded with boxes, ton bags and trailers full of olives.

not noticeably rustic!

The first thing we realised was that we had been unnecessarily careful about twigs and leaves in our crates of fruit. A huge trailer was being emptied as we arrived. There was so much foliage and so many lumps of tree in the load that I thought at first it was post-sorting residue!

Several men wearing boiler suits with the Almazara logo on them were striding about the place, but it was not at all obvious what we had to do. The black door on the right was closed. Steps led up to another door in front of us, so we went to take a look.

Great lumps of tree with a few olives

A clinically white room. On the right were three huge, stainless steel vats with taps on them. A couple of older, unremarkably dressed people were filling five litre bottles of oil from them. The wall facing us was a huge window onto a room where more huge vats gleamed in a very un-rustic sort of fashion. Notices forbidding something were taped to the wall, to the window and to the vats. (Wonky. Always wonky. No matter where you are, the signs are never straight. The effort involved to ensure maximum outrage to the compulsive must be gargantuan and unrelenting.) Whatever it was that they were so busy forbidding in 36 point Ariel Bold, clearly required multiple postings of the same warning. What a shame we had no idea what had their knickers in such a knot!

Nobody said a word to us. I decided to take advantage of the facilities on the left, and try to look as if that was the only reason I had broached the forbidden room.

Forbidden to strangle the dolphins. Read the copy of the notice in the ladies’. Or was it Forbidden to contaminate the crack? Forbidden to distract the minions? It is such a nuisance when you have some, but not all of the vocabulary you need! I decided that I was unlikely to infringe any rules if I just washed my hands and left.

Geoff decided to go and take some photographs. Forbidden to divulge the secret process? while I investigated a portacabin that seemed to be important. Men in boiler suits and local old boys seemed to be moving in and out of it, a little like wasps giving away the location of their nest.

Spanish people, I have noticed, are great at asking questions like “Are you off shopping?” or “Are the chickens laying well?” or at stating the blindingly obvious “I am having a bit of a walk.” There are some daring stunts of combined question/statement banter “I am irrigating. Are you picking olives?” This last, usually delivered by an old boy sloshing about in the water channel that runs past the tree you are harvesting. However, if you need to find out what the procedure is for getting your olives pressed without doing the unmentionable forbidden thing, nobody will meet your eye and you are left in the sort of dreamlike, apparently invisible, helpless spectator mode so loved by experimental film makers.

Eventually, I cornered a rather pleasant-looking young man.

Wearing umpteen layers, he is still thin

“It’s our first time here. What do we need to do?”

“Have you been picking your olives? It’s cold, isn’t it? Look how many layers of clothes I am wearing!”

I admired his boiler suit, fleece, scarf, jumper, t-shirt, vest and underpants – yes, really, he felt it was necessary to peel back the layers until I could see his beautiful, tanned olive-skinned hip and the waistband of his no doubt trendy underwear – and wondered what he would do if I reciprocated. Forbidden to flash your smalls? I thought better of it.

“This one is broken, but you can use that one. It will be a bit of a wait.”

“How long?”

“You will be after him. Maybe half an hour.”

He took our details and tapped them into his computer.

We decided half an hour would be a good opportunity to mooch about and get the hang of what was going on.

Inside a three-sided, chest-high barrier, was a huge hole in the ground, covered by what looked like a cattle grid. A large truck was backed up to the open side, emptying a pile of twigs, branches, foliage and olives onto the grid. Several men with brooms and rakes were encouraging the pile through the bars of the grid, removing the largest of the branches onto an untidy pile at the side.

Encouraging the olives through the grid

From the hole beneath, which turned out to contain an enormous hopper, the leaves, twigs and olives were taken by a conveyor belt or three to a large, yellow skip thingey, high above the ground. It became apparent that this structure contained some kind of sorting and blowing arrangement, as twigs and rubbish flew out of an aperture on the side and, via another conveyor, onto a vast pile, which was periodically cleared by a man with a JCB.

a huge pile of detritus

The olives dropped out of an opening at the bottom and were taken by further conveyor belts to a hopper near the portacabin. One of the employees removed a small plastic bag of olives from the hopper, stuck a barcode on it and added it to a bucket of similar bags. Then the hopper was emptied onto yet another conveyor, which took the olives still further upward into the farthest reaches of the mass of machinery.

In the distance, behind the huge shed, piles of brownish, sandy coloured waste were what we presumed was left after the oil had been extracted. The crushed stones and skins, we believe, are used to make bio-fuel. The foliage and twigs may be used for compost or pellet burner pellets. It seems that very little actually goes to waste.

a mysterious and probably significant part of the process

It was quite hypnotic watching all the activity and working out what was happening. The smell of olives was everywhere and more and more vans, cars, trucks and farm vehicles arrived, dropping off crates and ton bags. Some of the customers were clearly employees of large olive growers, some were elderly ladies in typical elderly Spanish peasant lady garb. Some were little old men with flat caps and bowed backs, who hardly seemed big enough to lift the crates they had stacked in the back of their beaten up furgonetas. One or two handsome, jeans-clad younger men strutted about, smoking and exchanging greetings with the middle-aged and elderly. It was all quietly convivial and relaxed, although everyone was busy and industrious.

After an hour and a half or so, it was our turn to throw our puny contribution into the hole. No problems with raking and sifting for us! Geoff took a quick picture of our olives disappearing up the conveyor belt. It was hard not to feel self-conscious and a little silly, but this momentous occasion needed documenting, not least so that I could include a few pictures here!

our olives ascend majestically!

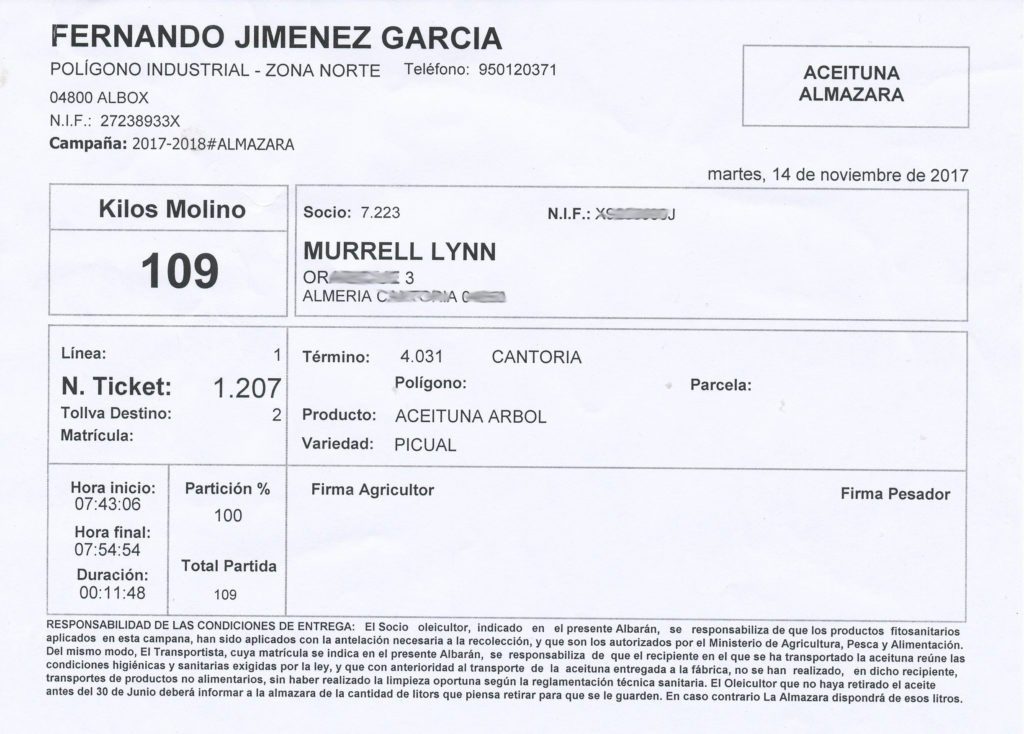

The Nice Young Man with the Underpants beckoned me into the portacabin. He printed out two sheets of paper, peeled a barcode off one of them and stuck it to a little bag of our olives. He asked me to sign and gave me one of the papers.

A friend had told us that the sample bags of olives are tested for oil yield, so that you get back the right amount of oil. Next year, we would like to have our own pressing, but this year’s crop went in with the big boys’ and the oil we received back was not specifically ours.

bagged, bar-coded and ready to go

“When will the oil be ready?” I asked him

“Middle of December.”

I was a little taken aback, but we decided we could ask again when we brought the next lot, just in case I had misunderstood.

“We have more to pick. What are your opening hours?”

“Whenever you like. Twenty-four hours.”

We ended up with three of these and a total of nearly 300kg of olives

We thanked him very much, picked our way through the bags, boxes and crates of olives that littered the car-park-cum-yard, the sheet of paper grasped triumphantly in my grubby hand.

We made two more trips to the Almazara, each time with the pickings of a couple of days. Whether it was pitch dark in the evening, or just getting light, the machines were clanking and whirring and the Nice Young Man was there. Eventually, I asked him how many hours he worked each day.

“Eighteen or twenty, for the duration of the harvest.”

“What do you do the rest of the year?”

“I work in bars or restaurants and I am a gigolo in a night club.”

“Did you say gigolo?” I asked casually.

“Yes.”

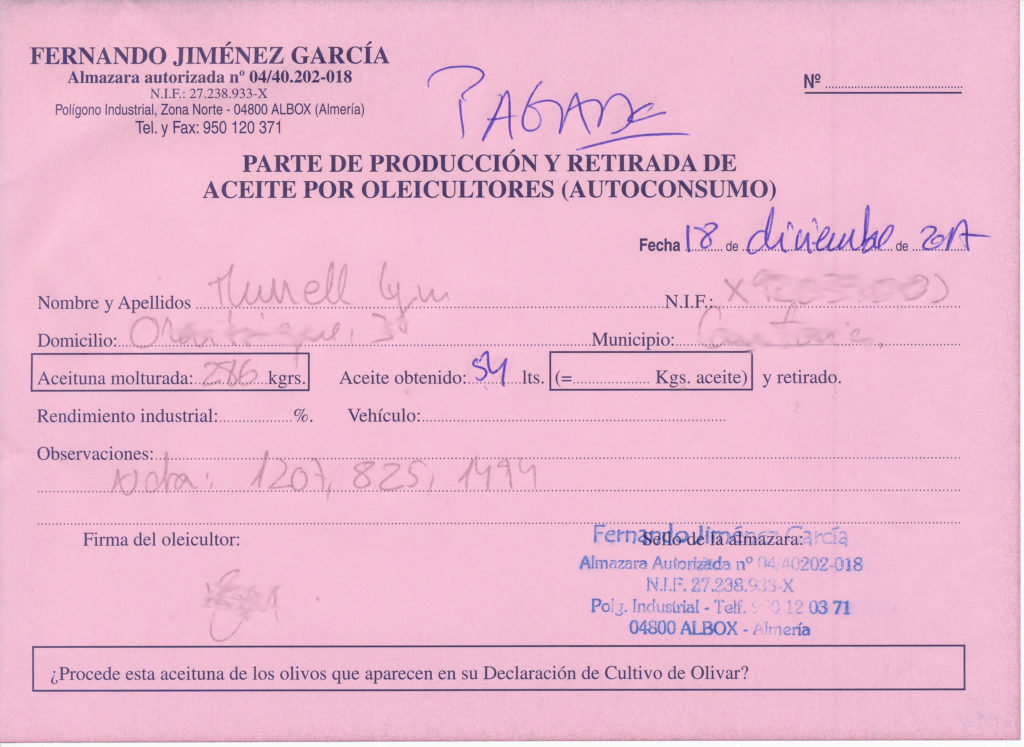

This says we took all our payment in oil – 54 litres

“I think that has a different meaning in English. You might want to be careful who you say that to.”

His interest was clearly piqued. I struggled with my schoolgirl Spanish.

“In English it is a young man who sells sex,” I faltered.

“Sells sex?”

“Well, er yes, like a boyfriend, but for money.”

I wished I had not started down this particular road. Did he think I was propositioning him, with his multiple layers, beautiful skin and trendy underpants?

“For money, eh?” He raised an eyebrow and smiled. “Por qué no?”

I did not stay long enough to explain the many reasons porque no. I shall look up gigolo in my Spanish/English dictionary and while I am at it, I may find out what exactly is forbidden at our local Olive Press.

Greeny gold liquid loveliness!